Multimedia Gallery

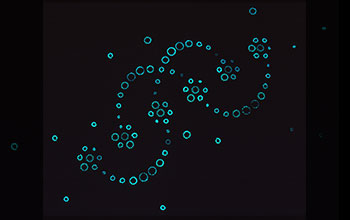

Bioluminescent bacteria glow brightly in this "Bioglyphs" painting

Bioluminescent bacteria glow brightly in this "Bioglyphs" painting (approximately 7 by 6 feet), created in 2002 by Angela Bowlds, a student from Montana State University Bozeman School of Art.

The painting was created as part "Bioglyphs", an exhibition of living bioluminescent paintings that brought science and art together in the form of a collaborative project involving students from Montana State University's School of Art and science and engineering students from MSU's Center for Biofilm Engineering (CBE).

More About This Image

"Bioglyphs" consisted of two exhibitions of living bioluminescent paintings created by teams of student and staff artists, scientists and engineers.

Microorganisms live all around us but we are rarely aware of their presence. The "Bioglyphs" exhibition allowed viewers to have direct sensory contact with a microscopic organism. Scientists were unsure of the exact identity of the bioluminescent organisms that were used in the exhibit, but they were believed to be single-celled, marine-environment bacterial isolate, probably of the Vibrio species. These bacteria only grow on a high-salt medium at relatively low temperatures--considerably lower than the internal temperature of the human body. Like many marine organisms, they produce blue light through a chemical reaction. Other Vibrio species such as Vibrio fischeri, will produce light after a certain number of organisms have accumulated. Why the light is produced by communities rather than by a single organism in these species is unknown, but the phenomenon raises questions about the nature of communal response and interaction.

In order to obtain the bacteria used in the exhibit, scientists from the CBE prepared plates with a nutrient medium that would sustain the bacteria for a limited period of time. Successful growth however, depended on numerous factors, not all of which could be controlled. How the bacteria would respond to an environment created for them was inherently unpredictable.

When the bacteria were transferred to Petri dishes, they were invisible, but within 24 hours, they rapidly multiplied and began to emit a blue light. Over the course of several days, light production peaked and then began to decline, as the available nutrient was used up. This life cycle heightens our awareness of resource limitations, as well as species-interdependency. [This copyright text was used by permission from the MSU-Bozeman Bioglyphs Project.] (Year of image: 2000)

Credit: ©2002 MSU-Bozeman Bioglyphs Project

Special Restrictions: Permission is granted to use this image for personal, educational or nonprofit/non-commercial purposes only. Credit information must appear with the image: ©2002 MSU-Bozeman Bioglyphs Project. Permission to use this image in a manner not stated here must be obtained from the MSU-Bozeman Bioglyphs Project contact, Peg Dirckx at peg_d@erc.montana.edu.

Images and other media in the National Science Foundation Multimedia Gallery are available for use in print and electronic material by NSF employees, members of the media, university staff, teachers and the general public. All media in the gallery are intended for personal, educational and nonprofit/non-commercial use only.

Images credited to the National Science Foundation, a federal agency, are in the public domain. The images were created by employees of the United States Government as part of their official duties or prepared by contractors as "works for hire" for NSF. You may freely use NSF-credited images and, at your discretion, credit NSF with a "Courtesy: National Science Foundation" notation.

Additional information about general usage can be found in Conditions.

Also Available:

Download the high-resolution TIFF version of the image. (10.6 MB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.

All images in this series

All images in this series