Multimedia Gallery

Physiology and Behavior Study (Image 9)

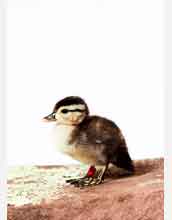

A wood-duck duckling. Wood ducks are one of several species that are the subject of research by Bill Hopkins, associate professor of fisheries and wildlife science at Virginia Tech. Hopkins and colleagues are conducting studies to determine how the physiology and behavior of female amphibians, turtles and birds affects their offspring, and the consequences these interactions may have for population health. [Image 9 of 14 related images. See Image 10.]

More about this Image

The behaviors of a mother strongly influence their young and will determine how they will live and thrive as adults. From the habitat they choose for nesting, the types of food they feed their young, the care they give to their eggs and their behavior toward and interaction with their new-born offspring--all of these behaviors will influence their young.

These non-genetic behaviors--called "maternal effects" by evolutionary ecologists--play a large role in determining the physical appearance of off-spring, their health and how they cope with life as adults.

Incubation behavior is a prime example of maternal effects in birds. Birds know they must maintain an optimal temperature during incubation in order for the embryos to properly develop. But they must also leave the nest periodically for other activities, such as feeding, thereby decreasing the incubation temperature. Leaving the nest could result in the loss of eggs because a decrease in incubation temperature of even a few degrees can effect offspring.

Sarah DuRant, a wildlife doctoral student working in Hopkins' lab, is studying how the incubation behavior of wood ducks affects their development before they hatch and whether or not it has lasting effects after hatching. DuRant is trying to determine if changes in the mother's incubation behavior may influence the development of the duckling's behavior, as well as their endocrine and immune systems--both vital for survival.

To conduct their experiments, Hopkins and his team installed nest boxes at a research site in South Carolina. The boxes were monitored throughout the breeding season and researchers removed some eggs immediately after they were laid for incubation tests in the lab. The borrowed eggs were incubated at different temperatures in the natural range that would occur if done by the mother. Hopkins and DuRant measured responses to different temperatures during development and examined the health of ducklings after hatching. The ducklings were then released near their original nesting site, to see how they would cope in the wild. Collaborative researchers from Auburn University and Georgia Tech monitored the duckling's behavior and determined the first-year survival and return rates.

As a result of their research, the team learned "that less than one degree difference in average incubation temperature is enough to strongly influence growth rates and endocrine responses during early life," says DuRant.

"This work will be important for conservation efforts because human-dominated landscapes can produce suboptimal habitat for nesting birds. When females are forced to spend more time away from the nest to find food, they spend less time incubating their eggs. Our work demonstrates that even moderate changes in a mother's behavior could be important to the success of her young," adds DuRant.

The project is a collaborative effort between researchers from Virginia Tech's department of fisheries and wildlife sciences and department of biological sciences, Auburn University, and the University of Georgia, and is funded by a large grant from the National Science Foundation. To learn more about this and other projects in the Hopkins lab, visit the lab website Here.

Credit: Lara Hopkins

Images and other media in the National Science Foundation Multimedia Gallery are available for use in print and electronic material by NSF employees, members of the media, university staff, teachers and the general public. All media in the gallery are intended for personal, educational and nonprofit/non-commercial use only.

Images credited to the National Science Foundation, a federal agency, are in the public domain. The images were created by employees of the United States Government as part of their official duties or prepared by contractors as "works for hire" for NSF. You may freely use NSF-credited images and, at your discretion, credit NSF with a "Courtesy: National Science Foundation" notation.

Additional information about general usage can be found in Conditions.

Also Available:

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (1.2 MB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.