Multimedia Gallery

Gamma-ray Burst Smashes a Record

Astronomers believe that a gamma-ray burst observed on Sept. 4, 2005, may have originated with the explosion of a star that lived and died some 13 billion years ago, not long after the big bang brought the universe itself into being.

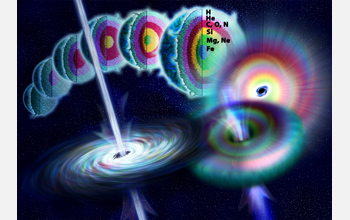

This particular star was a hulking specimen that had at least 30 times the mass of our own sun, which made it quite a bit bigger than almost any star that exists today. Nonetheless, it was destined for a very short life. Because of the star's huge mass, gravity caused the hydrogen gas in its core to become extraordinarily hot and dense, which in turn made the thermonuclear reactions there extraordinarily fierce. Soon, all the hydrogen in the core had been converted to helium. Then, when the helium "ash" became dense enough and hot enough, it, too, ignited to form elements such as carbon, nitrogen and oxygen.

Indeed, this cycle was repeated again and again, until the interior of the star acquired a kind of onion structure. First there was an outer shell where hydrogen was fusing into helium. Then inside that, there was a shell where helium was burning. Then came shells for carbon, oxygen and nitrogen, silicon, and magnesium and neon. And finally, at the very center, there was a core of iron nuclei--the ash from all the layers of thermonuclear fusion above it.

But iron was the end. Iron nuclei can neither fuse nor fission; they are as stable as atomic nuclei can get. So the iron in the core of the star could only accumulate. Before long, in fact, this steady accumulation of iron took the core through a kind of gravitational tipping point--whereupon it suddenly and catastrophically collapsed to form a black hole. The resulting release of energy quickly tore the star apart.

Such explosions are actually fairly common in the universe today; we know them as "supernovas." But unlike many supernovas, which tend to produce spherical blast waves, this one seems to have focused most of its explosive energy into two back-to-back jets of ultra-high-energy particles and radiation. Astronomers believe that this may have been the result of gas from the core that tried to fall into the black hole, but couldn't because it was rotating too fast. Instead, the gas settled into a very rapidly rotating "accretion disk" that surrounded the hole like a flattened donut. Only the gas around the inner rim of the disk could spiral into the hole. And when it did, it released vast amounts of energy that had no way to escape--except along the axis of the disk. Thus the back-to-back jets.

This image accompanied NSF press release, "Gamma-Ray Burst Smashes a Record."

Credit: Nicolle Rager Fuller, National Science Foundation

See other images like this on your iPhone or iPad download NSF Science Zone on the Apple App Store.

Images and other media in the National Science Foundation Multimedia Gallery are available for use in print and electronic material by NSF employees, members of the media, university staff, teachers and the general public. All media in the gallery are intended for personal, educational and nonprofit/non-commercial use only.

Images credited to the National Science Foundation, a federal agency, are in the public domain. The images were created by employees of the United States Government as part of their official duties or prepared by contractors as "works for hire" for NSF. You may freely use NSF-credited images and, at your discretion, credit NSF with a "Courtesy: National Science Foundation" notation.

Additional information about general usage can be found in Conditions.

Also Available:

Download the high-resolution JPG version of the image. (1.2 MB)

Use your mouse to right-click (Mac users may need to Ctrl-click) the link above and choose the option that will save the file or target to your computer.