U.S. South Pole Station

Supporting Science

NSF Station 1975

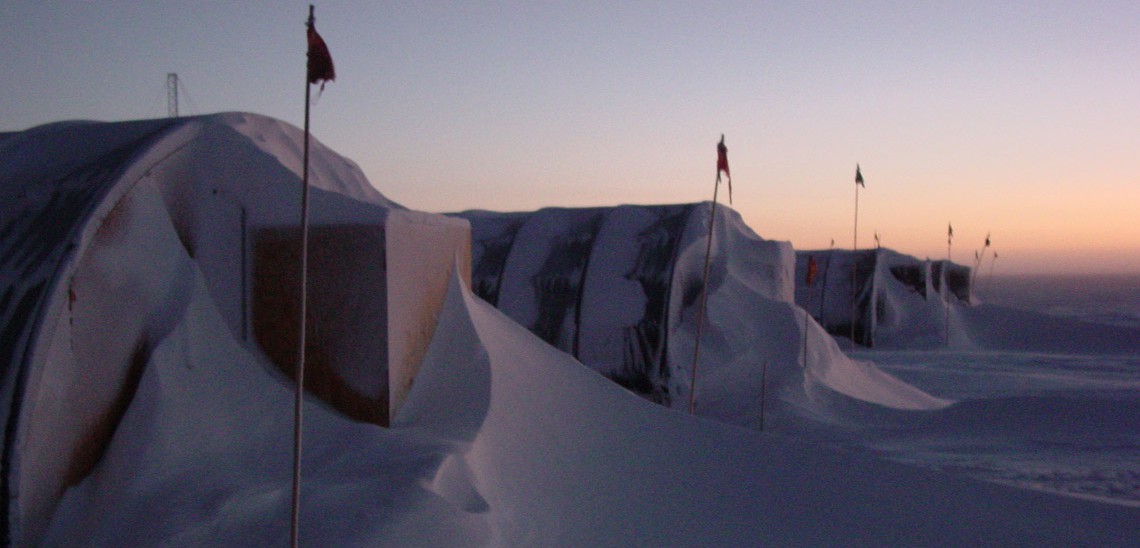

Drifting snow partly covers NSF's 1975 South Pole station, seen here in 1999

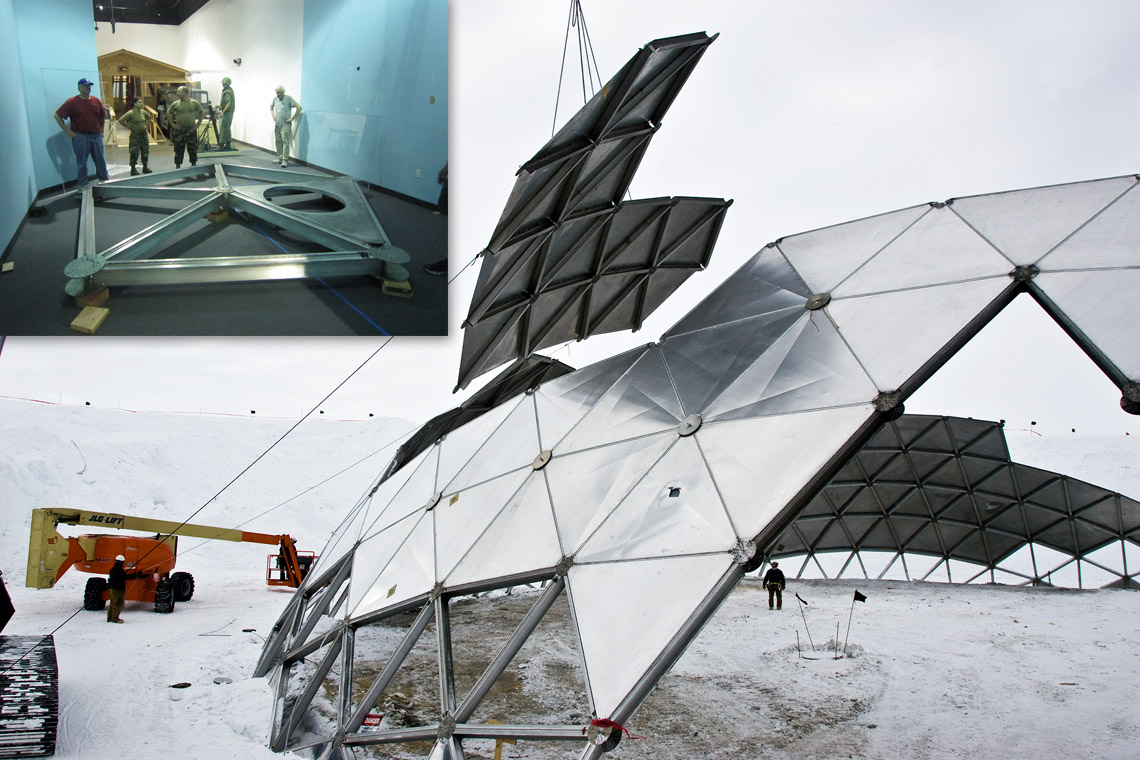

The geodesic Dome at Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station was deconstructed during the 2009-2010 austral summer and portions relocated to the Seabee Museum in California (inset)

NSF Station 1975 Photo Gallery

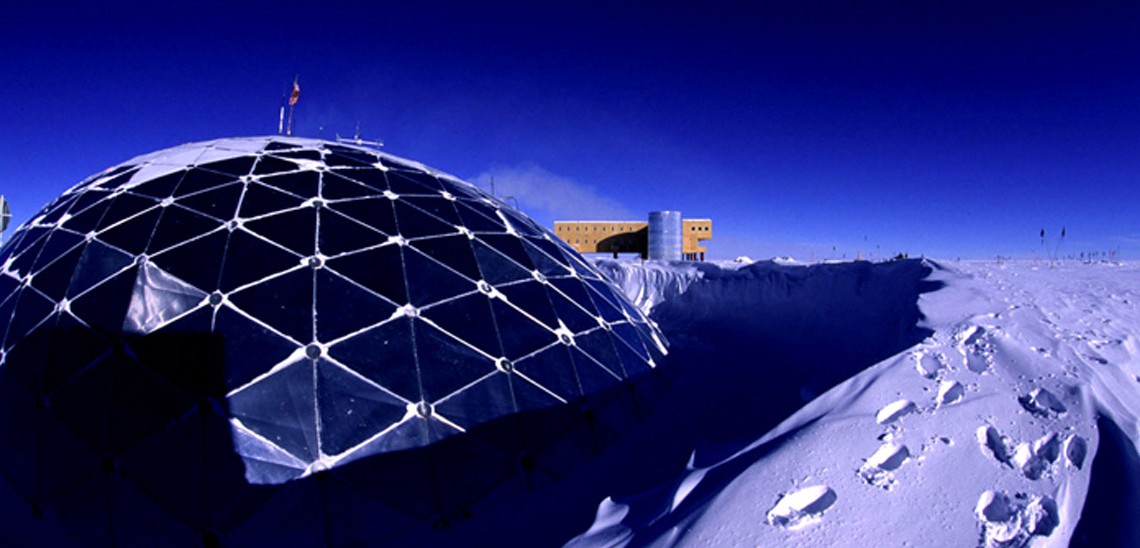

When this photo was taken in 1999, drifting snow had covered much of the dome of the South Pole station. The entrance was at ground level when the station was completed in 1975.

When this photo was taken in 1999, drifting snow had covered much of the dome of the South Pole station. The entrance was at ground level when the station was completed in 1975.

Credit: Josh Landis, NSF Footprints track through the snow that has drifted up around the dome, Removing that build-up, an endless task, is not necessary at the new station, which is elevated above the ice sheet and can be raised on its supports over time.

Footprints track through the snow that has drifted up around the dome, Removing that build-up, an endless task, is not necessary at the new station, which is elevated above the ice sheet and can be raised on its supports over time.

Credit: National Science Foundation, USAP The Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, which opened in 1975 and is still partly in use, is a two-part structure. The familiar geodesic dome - shown here during construction in the 1972-1973 austral summer season - is an enormous roof that provides shelter for smaller buildings that sat beneath the 55-foot-high, 165-foot-wide dome. Some of the buildings already have been removed as the new station rises outside the dome.

The Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, which opened in 1975 and is still partly in use, is a two-part structure. The familiar geodesic dome - shown here during construction in the 1972-1973 austral summer season - is an enormous roof that provides shelter for smaller buildings that sat beneath the 55-foot-high, 165-foot-wide dome. Some of the buildings already have been removed as the new station rises outside the dome.

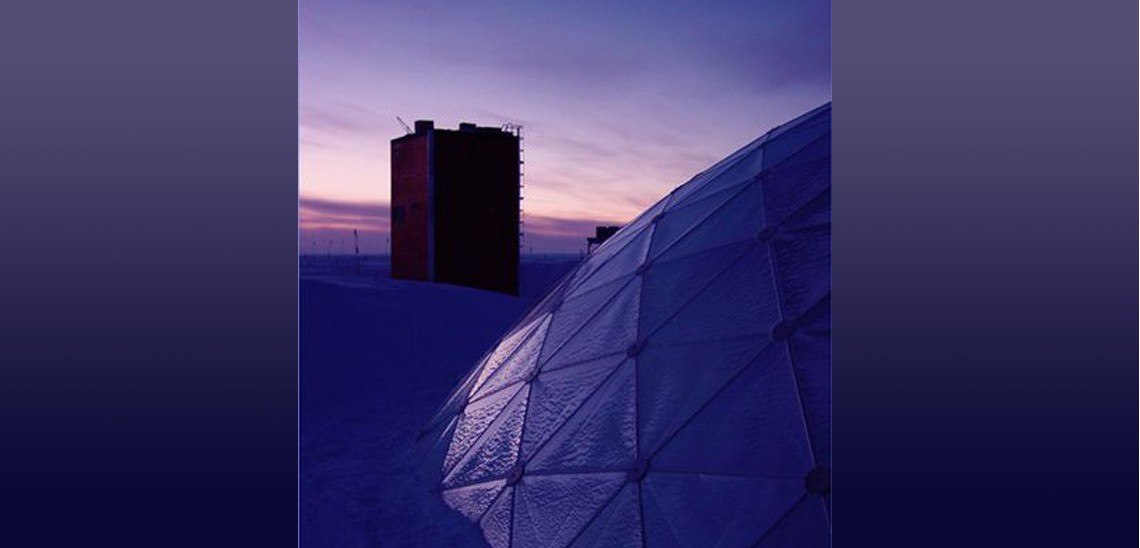

Credit: Lee Mattis, NSF The sun sets over the dome (foreground) and Skylab, one of the buildings that will be decommissioned when the 1975 station is replaced. Days and nights stretch for roughly six months each at the bottom of the world.

The sun sets over the dome (foreground) and Skylab, one of the buildings that will be decommissioned when the 1975 station is replaced. Days and nights stretch for roughly six months each at the bottom of the world.

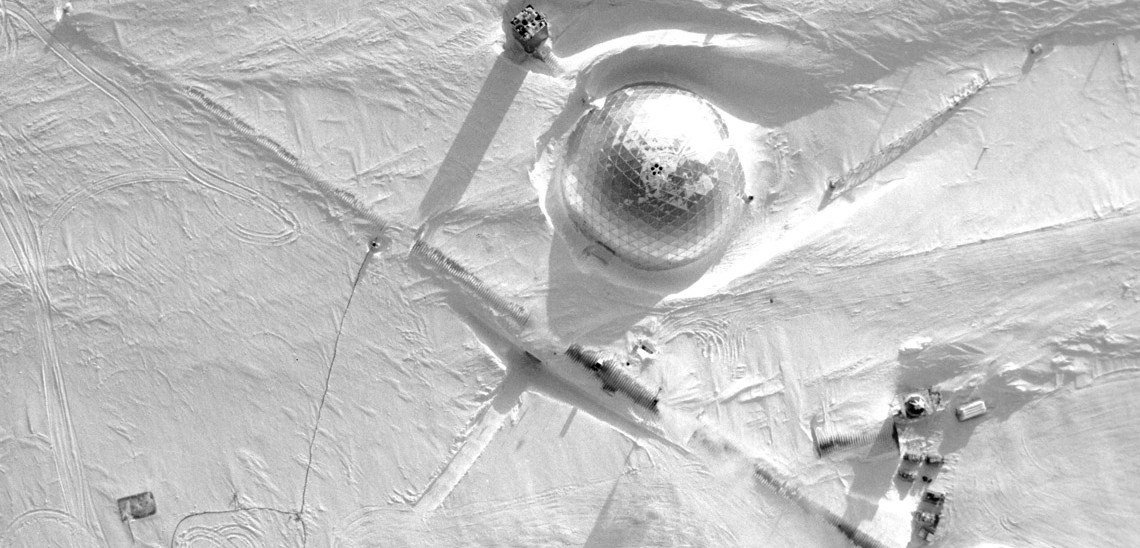

Credit: Jonathan Berry, NSF An overhead view of the geodesic dome and support tunnels taken before construction began on the elevated replacement station. The location of the new station is in the lower left quadrant of this 1992 photo.

An overhead view of the geodesic dome and support tunnels taken before construction began on the elevated replacement station. The location of the new station is in the lower left quadrant of this 1992 photo.

Credit: PH1 Edward Martens, U.S. Navy Ice forming on the support structure of the tunnel that provides access to the dome takes on fantastic crystalline shapes that can resemble hieroglyphic symbols. When the station was built in 1975, the entrance to the dome was at the surface of the ice sheet, but snow and ice accumulation eventually required the access tunnel to be dug.

Ice forming on the support structure of the tunnel that provides access to the dome takes on fantastic crystalline shapes that can resemble hieroglyphic symbols. When the station was built in 1975, the entrance to the dome was at the surface of the ice sheet, but snow and ice accumulation eventually required the access tunnel to be dug.

Credit: Peter West, NSF Taken during the construction of the dome, this photo shows the support structure rising from the ice sheet and forming a geometric abstraction against the blue polar sky. In time, the triangular spaces were filled with a metallic covering to shelter the buildings beneath the dome.

Taken during the construction of the dome, this photo shows the support structure rising from the ice sheet and forming a geometric abstraction against the blue polar sky. In time, the triangular spaces were filled with a metallic covering to shelter the buildings beneath the dome.

Credit: John Perry, U.S. Navy Seabee, NSF By early 2006, very little remained under the dome of the 1975 South Pole station. Where three modular buildings once stood, relics of 30 years of human occupation were awaiting reuse or recycling.

By early 2006, very little remained under the dome of the 1975 South Pole station. Where three modular buildings once stood, relics of 30 years of human occupation were awaiting reuse or recycling.

Credit: Peter West, NSF The U.S. flag flutters over holes built into the roof of the dome. The five circular openings provide ventilation, preventing heat build-up that would melt ice on the interior, threatening the structures below.

The U.S. flag flutters over holes built into the roof of the dome. The five circular openings provide ventilation, preventing heat build-up that would melt ice on the interior, threatening the structures below.

Credit: National Science Foundation, USAP Korean War vintage Jamesway huts await occupants. Named for their inventor, Jamesways were developed at portable shelters and have been used in the U.S. Antarctic Program for decades. At the pole, they served as 'summer camp' accommodations as the number of seasonal residents exceeded space available under the dome.

Korean War vintage Jamesway huts await occupants. Named for their inventor, Jamesways were developed at portable shelters and have been used in the U.S. Antarctic Program for decades. At the pole, they served as 'summer camp' accommodations as the number of seasonal residents exceeded space available under the dome.

Credit: Patrick Hovey, NSF In June 2004, the U.S. flag, backlit by aurora australis or Southern Lights, flies at half-staff atop the geodesic dome in memory of former President Ronald Reagan. The flag was also lowered following the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and after the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003.

In June 2004, the U.S. flag, backlit by aurora australis or Southern Lights, flies at half-staff atop the geodesic dome in memory of former President Ronald Reagan. The flag was also lowered following the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and after the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003.

Credit: J. Dana Hrubes, Space Sciences Laboratory, South Pole Station

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations presented in this material are only those of the presenter grantee/researcher, author, or agency employee; and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.